A brief cover of the paleomicrobiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis is caused a by a group of

bacteria that are closely phylogenetically related called the

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. They are slow growing aerobic

gram positive bacilli that due to its high lipid content in its one

phospholipid bilayer, requires stain methods that facilitate the

dye into their cell wall, such as the heat method of Ziehl Neelsen

staining. It is estimated by the WHO that approximately one third of

the world population have latent TB infections but only 5 to 10

percent of these individuals will develop the disease in their

lifetime.

Skeletal Material

It was recently thought that TB was

likely transferred to humans during the Neolithic period associated

with increasing sedentary lifestyles and domestication of cattle,

perhaps transferred from Mycobacterium bovis (Iseman 2478 : 1994),

but with the exception of Mycobacterium canetti, members of the MTBC

group do not show horizontal gene transfer (Gagneux 852 : 2012) most

of the genetic differences in the MTBC are due to deletions. Thus

comparison of human M tuberculosis and M bovis indicate that the M

bovis genome is around 60 000 base pairs smaller than the human M

tuberculosis genome, thus the human M tb lineage is older than M

bovis and this also suggest TB in humans predates the Neolithic

period (Gagneux 852 : 2012).

TB in the bone is the result of a post

primary tuberculosis spread and is a chronic process, thus features

remodelled marginal erosive lesions. In cases of active TB, 3 to 5 %

of individuals develop bone lesions (Holloway et al 2011). Newly

formed woven bone can be distinguished from mature lamellar sclerotic

changes, that can suggest healing. The presence of woven bone

indicates lesions active at time of death while sclerotic changes

changes signal an inactive disease process (Roberts & Buikstra 88

: 2003). Mycobacterium bovis, is more likely to cause skeletal damage

and is potentially up to 20 times more likely to lead to bone and

joint tuberculosis in children.

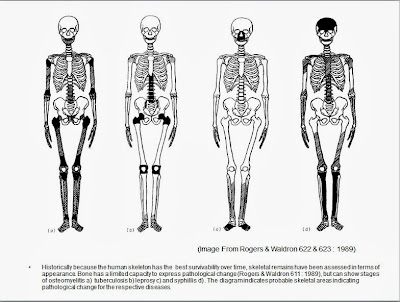

Other diseases that show up in skeletal

material include osteomyelitis, syphilis and leprosy. Indicated in Figure A.

|

| Figure A |

Because these diseases leave evidence

in skeletal material much attention in paleopathology focused on

these diseases in the historical record. Such classifications tend to

be on the basis of most probable cause and when collections of

skeletal material demonstrating pathology classifications has been re

examined there have been many examples the initial classifications

being challenged. (Picture from Infections in Palaeopathology :

The Basis of classification according to most probably cause. By

Juliet Rogers and Tony Waldron 1989).

Donoghue (2011) describes the gradual

inclusion of bone specimens for TB analysis by DNA techniques that

did not show bone pathology, the initial studies took this as

indications of haematogenous spread of tuberculosis bacilli. There

have been cases where not MTBC aDNA was found in bones demostrating

pathology, most likely attributable to poor DNA preservation but at

least one study has found brucellosis DNA sequences, IS6501 in

vertebra negative for IS6110 and M bovis sequences oxyR pseudogene

and mpt40 that showed pathology that could easily be classified as

typical of M tuberculosis (Mutolo 2011).

Up until the 1960's it was still being

argued that there was no Pre Columbian tuberculosis on the basis of

skeletal material.

The cut off for pre-Columbian contact is

1492 AD, the exact date of the mummy is not given but is around this

time. It is significant because an early theory for the absence of

skeletal remains showing TB in the Americas was that TB was

introduced by European contact, and was still being argued about in

the 1960s by Dan Morse. An interesting part of his argument was that

North Americans lived in small population densities that would not

have supported the disease, making a comparison to then contemporary

indian populations, he calculated that 2.24 percent of skeletal

material should present evidence of bone tuberculosis and 0.67

percent with vertebral involvement (Roberts & Buikstra 2003 :

188).

The study conducted by Corthals et al

(2012), titled “Detecting the immune system response of a 500 year

old inca mummy” uses PCR amplification to detect the presence of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and “shotgun proteomics” to detect the

protein expression in buccal swabs and cloth samples from 500 year

old Andean mummies, two young children and an adolescent girl.

The mummies were buried 25 meters from

the 6739 metre summit of Llullaillaco, a high elevation volcano in

the province of Salta, Argentina. They were buried 50 cm underground

and packed with volcanic ash. This ash inhibited the growth of

decomposing bacteria & fungi, functioned as a barrier to moisture

and airtight with snow and the freezing temperature, the corpses

were preserved by the combination of mild humidity, anaerobic

environment and natural disinfectants (see figure B).

|

| Figure B |

The paper describes the three children

as being sacrificed to Pachamama, the earth goddess, in the ritual of

Capacocha. Subcutaneous fat in the bodies was converted to soap by a

process called adipocere.

The presence of pathogenic

Mycobacterium was indicated as being probable by PCR using primers

for the genus Mycobacterium and primers belonging to species in the

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. For a lot of DNA techniques the

significance of the presence of Mycobacterium DNA is questionable,

part of the natural soil flora, a contaminant or an indication of the

pathogen. Early work trying to confirm the presence or absence of a

pathogen used a fragment of the M. tuberculosis complex MTBC

specific repeat element, but this is for the whole MTBC complex, not

just Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Because of the good preservation of

the material the study has been able to use a wide range of primers,

including species specific primers, as indicated in this figure

(figure C).

|

| Figure C |

It has been argued that the

mycobacterium cell wall properties can potentially enhance the

preservation of nucleic acids (Donoghue & Spigelman 2006) but

Wilbur et al 2009 argues that the same cell wall properties will

enhance its degradation, so this is an issue to be resolved. More

recent papers describe the use of a MALDITOF, Matrix Assisted Laser

Desorption Ionization Time of Flight, mass spectrometry technique

that detects the presence of the tuberculosis using the lipid

components of the cell wall, mycolic acids. This is not without its

issues, but it is potentially able to be used to detect Mycobacterium

tuberculosis pathogen in less well preserved skeletal material.

The Corthals et al (2012) paper wanted

to establish whether or not the mummy of the adolescent female had an

active infection at the time of her sacrifice. It would be

interesting to speculate whether this influenced the process of her

being used in the sacrifice. The proteonomics technique used by the

study was able to match up the mass spectrum of proteins from the

lip swab sample of the 15 year old adolescent female to a library of

immune system proteins.

They found normal serum proteins and

some proteins not normally present in blood or saliva but are

consistent with immune response to infectious disease. These

included,

- Cathepsin G, a specialized neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte serine protease found in the azurophil granules, with its function liked to pathogenesis of diseases associated with inflammation and neutrophil infiltration of the airways.

- Alpha antitrypsin, a marker of chronic lung infection, a strong indicator of mycobacterial infection.

- Neutrophil defensin 1 and 3 are part of the defensin family of cysteine rich cationic proteins found in leukocytes and are specifically associated with macrophages involved in lung tissue inflammation response.

- Proteins including apolipoproteins A1 & A2 and transthyretin, which are expressed in chronic and acute lung inflammation, and can be used as monitoring biomarkers for pulmonary related diseases.

After the proteomics technique the

paper presents a PCR and a maximum likelihood phylogeny to indicate a

higher probability that presence of Mycobacterium belonged to the

pathogenic MTBC complex.

The ancient lineage of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis is suggested from a study on a pre-Pottery Neolithic

site in Atlit Yam in the Eastern Mediterranean dating from around

9250 to 8150 Before present era, bones belonging to a woman and

infant demonstrated morphological changes, the detection of ancient

DNA and MTBC specific cell wall lipid biomarkers (Donoghue 2011).

Helen Donoghue (Donoghue 82 : 2008)

describes the use of cell wall lipid biomarkers for the purpose of

identifying members of the MTBC, with the advantage that the lipid

biomarkers are more stable, potentially lasting longer than DNA and

the methods used, HPLC and Mass spectroscopy are sensitive enough for

direct detection.

There are issues with the use of lipid

biomarkers for identification of members of the MTBC, although the

recent mycoloyl arabinoglactan- peptidoglycan complex is known,

ancient MTBC mycolic acids as synthesized are potentially different

due to adaptive evolution (Mark et al 112 :2011) and will undergo

chemical reactions post mortem thus over time will change the mass

spectrum peaks and fragment identification. The images on the screen

are from Mark Lazlo's et al (2011) paper “Analysis of ancient

mycolic acids by using MALDI TOF MS: response to “Essentials in the

use of mycolic acid biomarkers for tuberculosis detection” by

Minnikin et al 2010. Lazlo is referenced by Helen Dononhue (2011) in

the detection of lipid biomarkers, the team is responding to a

critique that the method is not sensitive enough for its application

for archaeological material.

When it was being argued that there was

no MTBC on the American continent, part of this argument was there

was a founder effect bottleneck and a low population density did

support endemic Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The low population

density argument is shown to be flawed with evidence of high density

sedentary Pre-Columbian populations in North America, without even

discussing Meso and South America but also a different picture of the

incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in ancient American

populations is emerging. Because of M tuberculosis biomarkers are

being found in archaeological material without demonstrating

pathological change the incidence of M tuberculosis in historical/

paleolithic populations is seen to be greater than previously

estimated (Donoghue 821 : 2011). This is accompanied by more recent

insights in the origin and evolution of M tuberculosis.

A paper by Holloway et al (2011) titled

Evolution of human tuberculosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of paleopathological evidence attempts to compare

all known cases of TB showing bone involvement from the range of 7250

BCE to 1899 and does a Chi squared test against the null hypothesis

that the frequency and location of bone lesions does not change over

time. The papers data was reported cases in literature, which yielded

530 TB cases from 221 gravesites reported in 151 references (Holloway

et al 407 : 2011). One of the interesting aspects of the paper was

its classification of sites in terms of pre urbanised, urbanised and

early modern time periods. In the Mediterranean early urbanization

is associated with Phoenician and Greek expansion, the beginning

date used was from 600 BCE (before the common era), while in Northern

Europe early urbanization is from 800 CE (common era). The paper

classifies early urbanization in the Americas as from 1500 CE, the

point of European contact. The paper produced a bar chart, comparing

time periods that shows a decrease in the frequency of skeletal

lesions over time, and a decrease in the frequency of involvement of

the spine with an increased involvement in other skeletal locations

(Holloway et al 411 : 2011). The significance of this can be

discussed with respect to an “osteological paradox” (Holloway et

al 414 : 2011), where to develop bone lesions the individual has to

be generally immunologically resistant enough and healthy enough to

survive a chronic condition. Thus this decrease in the frequency of

bone lesions could mean that the frequency of individuals with

sufficient immunological resistance has decreased. They argue that

because the average age of death was the same in all three time

periods that this is unlikely and describe a general evolutionary

process of decreased virulence of bacteria over time, although the

cause of death may not have been due to TB.

|

| Figure D |

This decreased virulence over time is

argued to be evidence of a form of sympatric speciation, a process of

coevolution that is often demonstrated by reciprocal transplant

experiments, where the performance of locally adapted pathogen

variants (sympatric) are compared to non locally adapted pathogen

variants (allopatric) ( Fenner et al 2 : 2013). An indirect way to

observe this is to look at the performance of pathogen variants when

the immune system of individuals of the sympatric host population is

disrupted. A paper by Fenner, Egger, Bodmer, Furrer, Ballif et al

2013 called HIV infection disrupts sympatric host pathogen

relationships in human tuberculosis has done this presenting a

statistical argument that HIV infection disrupts sympatric host

pathogen relationships in human tuberculosis. Currently Mycobacterium

exists in six main phylogenetic lineages associated with geographical

regions with sympatric human populations. Transmission tends to occur

in higher frequency in sympatric host pathogen combinations and these

associations remain in international cosmopolitan situations. The

Fenner et al study focused on 233 European born patients from a

population of 518 patients (21.6% had HIV) and defined a sympatric

host-pathogen relationship as infection with lineage 4 and allopatric

as infection with any other lineage. From this group of 233 European

born patients, 36 had HIV and of these individuals 9 had an infection

with a non lineage 4 Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain (Fenner et al

4 : 2013).

|

| Figure E |

Using a multivariate analysis there was a statistically

significant associated between HIV infection and infection by

allopatric M tuberculosis (unadjusted OR 7.0, 95% Confidence interval

2.5 -19.1, p value less than 0.0001). It also found that the strength

of the association between HIV infection and allopatric lineage

increased as CD4 T cell count went down (Fenner et al 6 : 2013). The

study has attempted to adjust for age, sex, frequency of travelling,

contact with foreign populations and other forms of immunosuppresion

and found that the only strong adjusted variable was repeated

travelling to low income countries with a decreased OR to 4.5 (95% CI

1.5 -13.6, p = 0.008). This data supports the idea of co-evolution

of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis and human host populations.

The time scale for the co evolutionary

relationship of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex with humans is

suggested by genome sequencing of M tuberculosis to be at least 2.6

to 2.8 million years ago, earlier than the range of Homo habilis (2.3

to 1.4 million years ago), suggested by synonymous sequence diversity

(Donoghue 825 : 2011), there is a possible material evidence of case

of TB in Homo erectus dating to 490 -510 000 years ago, from a

partial skeleton found in western Turkey (Donoghue 826 : 2011) .

The common image of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis, with very good reason, is as a scourge of high density

population centers characterised by the conditions of the early

industrial revolution (20th century) and urban populations

characterised by poverty. It is the medical reasoning for

antispitting laws that were enforced by New York City around 1910,

recently Waltham Forest Council in Britain (Paul Cocozza, from The

Guardian, September 2013) fined spitters and there is currently

an anti spitting Bill is being introduced in the Phillipines. But

given its long association with humans, predating the Neolithic, the

predominant conditions providing the evolutionary selection pressure

on it would be different from those now.

These pre Neolithic conditions would be

low density populations, that are composed of small, groups organised

around kinship structures that are predominantly mobile (Donoghue 826

: 2011). Because of this the organism would be under selection

pressure to survive through the lifetime of the individual host, with

transmission occurring from adults with reactivation of the disease

to other individuals, including infants with immature immune systems.

Reactivation would occur in situations of nutritional deprivement,

age related failing immune systems, and physical and mental stress

(Donoghue 826 : 2011). As such the organism would be selected towards

a quasi-commensal host pathogen relationship, with increased latency

in the majority of cases, over time there would be co evolutionary

processes leading to sympatric host pathogen relationships.

Conclusions

One of the insights that this model

provides is that given the increased population density, with a

greater opportunity for transmission, the selection pressures

favoring latent infection would be reduced and so selection pressures

should favor an increased bacterial virulence (Donoghue 827 : 2011).

There is evidence of evolutionary modern lineages that induce lower

levels of early inflammatory response and faster progression to

active disease (Donoghue 827 : 2011).

The use of antibiotics is a selection

factor, and most papers describe the mutation rates of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in resistance to line 1 antibiotics, isoniazid,

rifampicin and ethambutol as within the range of 1 X 10^-7

(ethambutol) to 2.3 X 10^-10 (rifampicin) and seem to describe

Mycobacterium tuberculosis as predominantly transferring antibiotic

resistance vertically, through generations (Gumbo 722 : 2013). In

lineage 2, which includes the Beijin strains, there is a prevalence

of MDR tuberculosis. It has been found that lineage 2 appears to have

a tenfold increased acquisition of rifampicin resistance compared to

lineage 4. This suggests another implication, that there are

different rates of multidrug resistance (antibiotic resistance) in

the different lineages.

|

| Figure F |

Comments.

Rabbit test models to determine when

treponemal dissimination found that in later stages of the disease

Treponomal DNA could not be isolated from the bone. Syphilis produces

marks of severe inflammation on long bones and cranium, deep erosions

and nodes that can be described as a moth eaten appearance and a

thickening of the long bones. Sectioned bone reveals a spongy

appearance with obliteration of the medullary cavities.

Holloway et al (2011) uses Pompeii as a

way of checking whether the frequency of lesions in the age and sex

distributions found in the cemeteries corresponded with the frequency

of lesions in living population age and sex distributions. It was

found that it did not differ in adult populations but did differ

significantly in sub adult (child) populations (Holloway et al 414 :

2011), this is why the Holloway et al (2011) paper only discusses

adult populations.

Mechanisms of action of antibiotics, for figure F.

Ethambutol inhibits arabinosyl

transferase involved in cell wall biosynthesis, the enzyme is coded

for by three homologous genes embCAB and resistance is associated

with mutation of these loci

Isoniazid is a peroxide producing drug

that relies on catalase activity to interfere with mycolic acid

biosynthesis.

Rifampic prevents transcription of DNA

dependant RNA polymerase, binds to beta subunit, resistance is

conferred by mutations of the rhoB gene that encodes

Pyrazinamide interferes with fatty acid

synthesis, lowering intracellular pH which inactivates fatty acid

synthase

Bibliography

Donoghue, Helen D. (2008). Chapter 6 :

Palaeomicrobiology of Tuberculosis. In D Raoult & M Drancourt

(eds). Paleomicrobiology : Past Human Infections. Published by

Springer-Verlag Berline Heidelberg. Pages 75 -97

Donoghue, H.D. (2011). Insights gained

from palaeomicrobiology into ancient and modern tuberculosis. In the

Journal of Clinical Microbiology Infectious Diseases. Volume

17. Pages 821 – 829.

Fenner, L; Egger, M; Bodmer, T; Furrer,

H; Ballif, M et al. (2013). HIV Infection Disrupts the Sympatric

Host-Pathogen Relationship in Human Tuberculosis. In PloS Genet

Volume 9, Index 3. e1003318. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003318

Gagneux, Sebastien. (2012).

Host-pathogen coevolution in human tuberculosis. In Philosphoical

transactions of The Royal Society. Volume 367. Pages 850 -859.

Gumbo, Tawanda. (2013). Biological

variability and the emergence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. In

Nature Genetics. Volume 45. Pages 720 -721.

Holloway, K.L; Henneberg, R. J; Lopes,

M de Barros & Henneberg, M. (2011). Evolution of human

tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

paleopathological evidence. In Homo- Journal of Comparative Human

Biology. Volume 62. Pages 402 -458.

Iseman, Michael. (1994). Evolution of

drug resistant tuberculosis: A tale of two species. In Proceedigns of

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America .

Volume 91. Pages 2428 -2429.

Mutolo, Michael ; J. Jenny, Lindsey;

Buszek, Amanda; Fenton, Todd W & Foran, David. (2012).

Osteological and Molecular Identification of Brucellosis in Ancient

Butrint, Albania. In the American Journal of Physical

Anthropology. Volme 147. Pages 254 -263.

No comments:

Post a Comment